I was chatting recently with a woman who is the accountant at a "seeker friendly" church. (If you are not familiar with that term "seeker friendly," it means the services primarily address people who are not yet Christians, so the messages are often very basic and evangelistic in nature.)

She said since the church adopted that format some years ago the growth has been astonishing. Many people have made committments to Jesus and the church has grown so much that it now needs larger facilities.

Wonderful! But on the other hand, she said, older members are leaving. She said people hang around for about five years and then go to the church up the street (well, a lot of them do). That church, she said, is more "discipleship" oriented, helping people who are already Christians to grow in their walk with God.

In discussing this we agreed that people just don't want to be stuck in first grade for the rest of their lives.

Anyway, in addition to kind of hurting the pastor's feelings, the people who are leaving her church are the ones who do most of the giving. She said it takes a few years for people to get into the habit of giving, and then when they do, they trot off to the church up the street.

I joked that maybe her church and the church up the street should enter into a partnership.

However, as I've been considering this since our chat, I'm not sure it is a big problem. Maybe churches should specialize, and maybe seeker churches should just consider that their ministry is reaching non-Christians and accomodate themselves to people leaving after a while. Or maybe seeker and discipleship churches really should form partnerships. At minimum, it seems to me that seeker friendly churches need to realize that if they want to hold on to people, they need to provide some paths for them to really deepen their walks with God.

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Sunday, May 28, 2006

Is Belief Intolerant?

I just had an annoying conversation with a high school student who said that "Christians are worse than everybody else."

They are? Christians are worse than everybody else?

In our discussion, it turned out she didn't mean they did bad things (though I was willing to concede that they may), but rather that they hold their beliefs to be true and other people's beliefs to be false, which, of course, made them intolerant.

Sigh. This is so discouraging.

Anybody who holds any belief about anything can be painted with the same brush. By believing something about a topic, you are automatically saying that different beliefs about the same topic are wrong - maybe not entirely wrong - but wrong in some respect. And if you believe someone is wrong, then according the current tortured definition of "tolerance," you are intolerant.

To take a simple example, if you believe 2 plus 2 equals 4, the corollary is that you do not believe they add up to 7 (you intolerant slime ball!). And if you believe 2 plus 2 equals 13, then you also believe the corollary, which is that those who hold that 2 plus 2 equals 4 are wrong. (You're still intolerant.)

Nor does it make the slightest difference how tactfully you express your belief; you are still saying - if only by implication - that someone else is wrong.

Some may say that they believe all beliefs are equally valid and worthy of respect. On the surface that sounds very broadminded, but in fact, it is precisely the same as any other belief. By saying all beliefs are equally valid and worthy of respect, you are saying that those people are wrong who believe only some beliefs are valid and only some beliefs are worthy of respect. (You're as intolerant as the rest of us.)

So, basically, this student's argument is that Christians are intolerant because they believe in Christianity. And logically, it also means that geographers are intolerant if they believe Pensacola is in Florida, and zoologists are intolerant if they believe snakes are reptiles, and - need I say this? - it means this student is intolerant because she believes Christians are intolerant. In short, it means everyone is intolerant any time they hold anything to be true, which is so dumb it's hard to imagine I'm wasting my time writing about it.

They are? Christians are worse than everybody else?

In our discussion, it turned out she didn't mean they did bad things (though I was willing to concede that they may), but rather that they hold their beliefs to be true and other people's beliefs to be false, which, of course, made them intolerant.

Sigh. This is so discouraging.

Anybody who holds any belief about anything can be painted with the same brush. By believing something about a topic, you are automatically saying that different beliefs about the same topic are wrong - maybe not entirely wrong - but wrong in some respect. And if you believe someone is wrong, then according the current tortured definition of "tolerance," you are intolerant.

To take a simple example, if you believe 2 plus 2 equals 4, the corollary is that you do not believe they add up to 7 (you intolerant slime ball!). And if you believe 2 plus 2 equals 13, then you also believe the corollary, which is that those who hold that 2 plus 2 equals 4 are wrong. (You're still intolerant.)

Nor does it make the slightest difference how tactfully you express your belief; you are still saying - if only by implication - that someone else is wrong.

Some may say that they believe all beliefs are equally valid and worthy of respect. On the surface that sounds very broadminded, but in fact, it is precisely the same as any other belief. By saying all beliefs are equally valid and worthy of respect, you are saying that those people are wrong who believe only some beliefs are valid and only some beliefs are worthy of respect. (You're as intolerant as the rest of us.)

So, basically, this student's argument is that Christians are intolerant because they believe in Christianity. And logically, it also means that geographers are intolerant if they believe Pensacola is in Florida, and zoologists are intolerant if they believe snakes are reptiles, and - need I say this? - it means this student is intolerant because she believes Christians are intolerant. In short, it means everyone is intolerant any time they hold anything to be true, which is so dumb it's hard to imagine I'm wasting my time writing about it.

Friday, April 28, 2006

Founding Anaheim

I recently read a book called "Men to Match My Mountains," by Irving Stone, about the history of the Western United States. Fairly good, but one thing that struck me as particularly interesting was the description of how the city of Anaheim, in Southern California, was founded.

The idea for the city, the book says, occured in 1857 to a group of Germans living in San Francisco who found the weather there a bit moist for their liking. (Obviously they were not looking for weather that reminded them of home.) So, 50 families each chipped in $750 to buy 1,165 acres in Southern California. They didn't all immediately move south, however. Instead, while they continued to live in the San Francisco area, they hired people in Southern California to divide up the land into 20-acre lots, build an irrigation canal, lay out a 40-acre town site in the middle, and fence in the community with willow trees. Then, when the vines began to bear fruit, the whole colony moved south to their new home.

But, because the properties were not identical in value, a committee assigned a value to each one, then the families drew lots for the properties. If they got a good lot, they paid the colony company extra money; if they got a poor lot, the company reimbursed them.

Clever... and fair.

I know that founding cities still happens occasionally (developers sometimes create cities near existing population centers, for example), but the idea of getting a group of likeminded people together to invest in a town and then carrying it out so methodically is pretty cool. Also, I thought the system the Germans adopted was very wise; they stayed up north - presumably working at their regular jobs - while they created jobs for themselves down south, then, when things were up and running, they just moved in and started working. Worth thinking about if you're planning to start a city. ;-)

The idea for the city, the book says, occured in 1857 to a group of Germans living in San Francisco who found the weather there a bit moist for their liking. (Obviously they were not looking for weather that reminded them of home.) So, 50 families each chipped in $750 to buy 1,165 acres in Southern California. They didn't all immediately move south, however. Instead, while they continued to live in the San Francisco area, they hired people in Southern California to divide up the land into 20-acre lots, build an irrigation canal, lay out a 40-acre town site in the middle, and fence in the community with willow trees. Then, when the vines began to bear fruit, the whole colony moved south to their new home.

But, because the properties were not identical in value, a committee assigned a value to each one, then the families drew lots for the properties. If they got a good lot, they paid the colony company extra money; if they got a poor lot, the company reimbursed them.

Clever... and fair.

I know that founding cities still happens occasionally (developers sometimes create cities near existing population centers, for example), but the idea of getting a group of likeminded people together to invest in a town and then carrying it out so methodically is pretty cool. Also, I thought the system the Germans adopted was very wise; they stayed up north - presumably working at their regular jobs - while they created jobs for themselves down south, then, when things were up and running, they just moved in and started working. Worth thinking about if you're planning to start a city. ;-)

Sunday, April 02, 2006

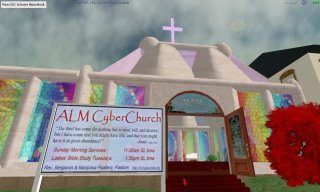

Attending Church with a Rabbit

Last Sunday at 11 a.m. I went to a new church. It was in a large building with stained glass windows, there was a good sermon and great music, a few people wandered around, there was some whispering and giggling, people lifted their hands in worship or knelt in prayer. All pretty normal for a contemporary-style church.

Last Sunday at 11 a.m. I went to a new church. It was in a large building with stained glass windows, there was a good sermon and great music, a few people wandered around, there was some whispering and giggling, people lifted their hands in worship or knelt in prayer. All pretty normal for a contemporary-style church.However... in the congregation was a large pink rabbit, a fairie, a woman with large butterfly wings and a man who kept jumping 15 or 20 feet into the air.

What is this weird place and how did I get here?

Well, I had read about a cyberworld called Second Life, a beautifully designed online place that in an approximate way resembles reality. In this world people can construct buildings, wander around, fly (without an airplane), meet people and party - especially party. And, in wandering around, I discovered that probably a lot of the partying is way beyond my level of comfort.

Anyway, I wondered if there was a Christian presence in this "world." I poked around a bit and found that, indeed, there is, so last Sunday I rushed home from my own church and attended the ALM CyberChurch. It was really great! I was welcomed at the door; the sermon was excellent; there was a fellowship time in an adjoining room after church, and I felt I had been in God's presence.

I shared this experience with my real-world fellowship, and after discussing it I think we all concluded that - with some reservations - cyberchurch is a useful tool, but some folks were a bit afraid that it might draw people in so much that they don't attend a real-world church. And one man felt because you wear a cyberbody that people would find it harder to get to know the real you.

Here are my thoughts on these objections:

- I think that probably every advance in communications has raised the possibility that people will withdraw from face-to-face contact and rely on a communications tool for their spiritual life. I'll bet that in Gutenberg's day some people were afraid that printing and distributing the Bible would cause people to withdraw and take their spiritual nourishment from solitary reading. The same might be said of radio or television ministries. And, frankly, I think those people have a point. It is possible some people will prefer a cyberchurch to a real-world church.

I'd generally prefer people don't abandon real-world churches since a cyberchurch is only an approximation of real people getting together in real bodies to worship God - though in some cases I think a cyber-church would be better than attending a dead real-world church.

- On the question of people hiding behind masks in the cyberworld, I think that may be true, but I think it probably works both ways. While your real face and manerisms can reveal much of your inner self to a discerning observer, I wonder if people in the cyberworld, who can choose their own bodies, aren't in a way choosing a body they believe expresses their deeper self. Also, I'd ask if the anonymity of the cyber-world doesn't make people feel a bit safer to reveal their inner selves since nobody need know who they are in the real world.

I don't think a cyber-church is for everybody. In fact, I think my visits will probably be just occasional, but I can think of some examples where they'd be a huge blessing:

1. For people who are physically isolated.

2. For those with health problems who are unable to leave their homes.

3. As an outreach to various groups of people. You could have a traditional church, a contemporary one, a punk one, a goth one, churches for various ethnicities. Whatever. I think you will find the cost of building facilities in the cyber-world compares favorably with the cost of building in the real world.

4. As a meeting place for Christians in closed countries for whom it is dangerous - or too distant - to get together in person.

5. For a mid-week fellowship group.

6. As a place for fellowships begun in the real world to continue when people move away. For example, a college Christian group could maintain itself when everybody graduates.

For a good introduction to the concept of cyber churches, see the Living Sounds Web page by the pastor of the ALM CyberChurch. If you'd like to visit the church, you need to sign up for Second Life (a basic account is free) and download the special Second Life browser. When you've done that, you can go directly to the church by clicking here: secondlife://Vine/173/75 .

Saturday, January 14, 2006

Meaningless, Meaningless!

What a peculiar document is the biblical book of Ecclesiastes!

"'Meaningless, meaningless,' says the Teacher. 'Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless.'" The Teacher starts with that happy thought and winds up with it, yet sprinkled throughout the book are hints of something that is not at all meaningless.

One commentator suggested the author is taking on the persona (perhaps from his own experience) of the worldly person. I think the author is addressing the person who perhaps believes in God in a casual sort of way, but who is really just a materialist. For his discussion the Teacher adopts this worldly viewpoint and drives it unrelentingly to its logical and hopeless conclusion, but all the time dropping hints of something different and better.

Everything, he says, is going to crumble, and you yourself will die. And he proceeds along those lines in kind of a stream-of-consiousness fashion, poisonously juxtaposing comments about enjoying yourself with comments about your ultimately meaningless end. Or, in another case, saying a stillborn is better off than the living because the child has never experienced the pain of life on earth, while in another section saying that a live dog is better off than a dead lion. So, is it better to be dead or alive? The materialist could follow either line of logic, and the Teacher explores them both: Life's meaningless so I might as well just die, or, Life's all I've got so I should enjoy it while I can.

Mr. Cheerful he is not.

But then he goes and drops these little clues all over the place about the spiritual.

Without God, he says, "who can eat or find enjoyment." God has "set eternity in the hearts of men;" "everything God does will endure forever;" what God has done is "so that men will revere him;" "God will bring to judgement;" when man dies "he takes nothing from his labor that he can carry in his hand;" "I know it will go better with God-fearing men;" "Remember your Creator in the days of your youth;" on death "the spirit returns to God who gave it." Plus, there are lots of proverbs instructing people in how to live and, of course, there is the conclusion that men should keep God's commands and that God "will bring every deed into judgement."

His everyday proverbs on how to live and about doing good make no sense if the ultimate spiritual end is destruction. In that case, why do good unless it is convenient? His comment that God will judge makes no sense if that judgement is limited to this life. Listen to him: "Although a wicked man commits a hundred crimes and still lives a long time, I know that it will go better with God-fearing men." I mean, he's just admitted that sometimes the wicked live a long time, and if, after that, everything is over, judgement makes no sense at all. And why should men revere or remember God if spiritually - not just physically - the good and bad are both going to just be dead? Why would God put eternity in the hearts of men if there was nothing besides death? Just to mock us? And listen to this big hint - Hint? More like a flat-out statement - that the Teacher drops when he says that on death "the spirit returns to God who gave it." Wow! That's what lives on! The spirit.

But even on the spiritual level, the emphasis is on God, not on what we can do. What God does "will endure forever" while nothing we do for ourselves will last for long. It makes me think of the gospel, that Jesus did it all for us. It's not our work. It's his. We just need to trust in him so that when our spirits return to God, as Ecclesiastes says, we will stand in our spiritual selves before God with our sins cleansed and ready to experience the joy of that eternity that God has placed in our hearts.

"'Meaningless, meaningless,' says the Teacher. 'Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless.'" The Teacher starts with that happy thought and winds up with it, yet sprinkled throughout the book are hints of something that is not at all meaningless.

One commentator suggested the author is taking on the persona (perhaps from his own experience) of the worldly person. I think the author is addressing the person who perhaps believes in God in a casual sort of way, but who is really just a materialist. For his discussion the Teacher adopts this worldly viewpoint and drives it unrelentingly to its logical and hopeless conclusion, but all the time dropping hints of something different and better.

Everything, he says, is going to crumble, and you yourself will die. And he proceeds along those lines in kind of a stream-of-consiousness fashion, poisonously juxtaposing comments about enjoying yourself with comments about your ultimately meaningless end. Or, in another case, saying a stillborn is better off than the living because the child has never experienced the pain of life on earth, while in another section saying that a live dog is better off than a dead lion. So, is it better to be dead or alive? The materialist could follow either line of logic, and the Teacher explores them both: Life's meaningless so I might as well just die, or, Life's all I've got so I should enjoy it while I can.

Mr. Cheerful he is not.

But then he goes and drops these little clues all over the place about the spiritual.

Without God, he says, "who can eat or find enjoyment." God has "set eternity in the hearts of men;" "everything God does will endure forever;" what God has done is "so that men will revere him;" "God will bring to judgement;" when man dies "he takes nothing from his labor that he can carry in his hand;" "I know it will go better with God-fearing men;" "Remember your Creator in the days of your youth;" on death "the spirit returns to God who gave it." Plus, there are lots of proverbs instructing people in how to live and, of course, there is the conclusion that men should keep God's commands and that God "will bring every deed into judgement."

His everyday proverbs on how to live and about doing good make no sense if the ultimate spiritual end is destruction. In that case, why do good unless it is convenient? His comment that God will judge makes no sense if that judgement is limited to this life. Listen to him: "Although a wicked man commits a hundred crimes and still lives a long time, I know that it will go better with God-fearing men." I mean, he's just admitted that sometimes the wicked live a long time, and if, after that, everything is over, judgement makes no sense at all. And why should men revere or remember God if spiritually - not just physically - the good and bad are both going to just be dead? Why would God put eternity in the hearts of men if there was nothing besides death? Just to mock us? And listen to this big hint - Hint? More like a flat-out statement - that the Teacher drops when he says that on death "the spirit returns to God who gave it." Wow! That's what lives on! The spirit.

But even on the spiritual level, the emphasis is on God, not on what we can do. What God does "will endure forever" while nothing we do for ourselves will last for long. It makes me think of the gospel, that Jesus did it all for us. It's not our work. It's his. We just need to trust in him so that when our spirits return to God, as Ecclesiastes says, we will stand in our spiritual selves before God with our sins cleansed and ready to experience the joy of that eternity that God has placed in our hearts.

Friday, December 30, 2005

The Philosophy of Elves and Dragons

I've been reading Christopher Paolini's Eldest, the second massive volume in his fantasy dragons-and-wizards trilogy begun with Eragon.

Reading their thoughts, I've come to the conclusion that despite their reputation for wisdom, you shouldn't put much stock in the philosophy of elves and dragons.

For example, on page 542 (hardback), Eragon is talking with the elf Oromis about elvish beliefs and the elf says, "I can tell you that in the millennia we elves have studied nature, we have never witnessed an instance where the rules that govern the world have been broken. That is, we have never seen a miracle. Many events have defied our ability to explain, but we are convinced that we failed because we are still woefully ignorant about the universe and not because a diety altered the workings of nature."

So, Oromis says the elves have witnessed events that "have defied our ability to explain," but nevertheless he is quite certain that those events are not miracles. And why couldn't those unexplained events be miracles?

Well, Oromis explains, the elves believe these events can't be miracles because the elves are still very ignorant of how the universe works. Hmmm... So elves don't believe a diety might work miracles because they're ignorant. Sorry, Oromis, the logic escapes me.

Then, to make it sillier, on the next page Oromis critisizes dwarfs for sometimes relying upon faith rather than reason. Methinks, Oromis, that if you want an example of faith, you should look in a mirror.

Oromis follows up by saying that if the gods exist, "have they been good custodians?" He then cites death, sickness, poverty, tyranny and other miseries.

But perhaps Oromis should consider the possibility that the inhabitants of the land may be at fault, and if the diety were to shackle the hands and feet and minds of people (and elves and dwarfs) to prevent them from committing evil, wouldn't Oromis complain that the diety is a tyrant, and that he enslaves his subjects? I think you might, Oromis.

Finally, Oromis says this athiestic view makes for "a better world" because "we are responsible for our own actions."

Oh, Oromis! The existance of God does not in the slightest take away our responsibility for our actions. If I steal from my employer does that mean I'm not responsible because my employer exists? Please don't talk nonsense, Oromis.

And then there's Eragon's dragon Saphira.

Eragon asks about her beliefs and Saphira replies, "Dragons have never believed in higher powers. Why should we when deer and other prey consider us to be a higher power?"

Uhh... I don't think Saphira had her coffee before replying. Let's just flip it around:

"Dragons have always believed in higher powers. Why shouldn't we when deer and other prey consider us to be a higher power?"

In other words, if Saphira is a higher power to the deer, why can't there be a higher power to Saphira?

Well, actually there is, and because writing the next 600-page book will no doubt take a while, author Christopher Paolini has plenty of time to get his subjects thinking straight. After all, he is a higher power to both Oromis and Saphira.

Reading their thoughts, I've come to the conclusion that despite their reputation for wisdom, you shouldn't put much stock in the philosophy of elves and dragons.

For example, on page 542 (hardback), Eragon is talking with the elf Oromis about elvish beliefs and the elf says, "I can tell you that in the millennia we elves have studied nature, we have never witnessed an instance where the rules that govern the world have been broken. That is, we have never seen a miracle. Many events have defied our ability to explain, but we are convinced that we failed because we are still woefully ignorant about the universe and not because a diety altered the workings of nature."

So, Oromis says the elves have witnessed events that "have defied our ability to explain," but nevertheless he is quite certain that those events are not miracles. And why couldn't those unexplained events be miracles?

Well, Oromis explains, the elves believe these events can't be miracles because the elves are still very ignorant of how the universe works. Hmmm... So elves don't believe a diety might work miracles because they're ignorant. Sorry, Oromis, the logic escapes me.

Then, to make it sillier, on the next page Oromis critisizes dwarfs for sometimes relying upon faith rather than reason. Methinks, Oromis, that if you want an example of faith, you should look in a mirror.

Oromis follows up by saying that if the gods exist, "have they been good custodians?" He then cites death, sickness, poverty, tyranny and other miseries.

But perhaps Oromis should consider the possibility that the inhabitants of the land may be at fault, and if the diety were to shackle the hands and feet and minds of people (and elves and dwarfs) to prevent them from committing evil, wouldn't Oromis complain that the diety is a tyrant, and that he enslaves his subjects? I think you might, Oromis.

Finally, Oromis says this athiestic view makes for "a better world" because "we are responsible for our own actions."

Oh, Oromis! The existance of God does not in the slightest take away our responsibility for our actions. If I steal from my employer does that mean I'm not responsible because my employer exists? Please don't talk nonsense, Oromis.

And then there's Eragon's dragon Saphira.

Eragon asks about her beliefs and Saphira replies, "Dragons have never believed in higher powers. Why should we when deer and other prey consider us to be a higher power?"

Uhh... I don't think Saphira had her coffee before replying. Let's just flip it around:

"Dragons have always believed in higher powers. Why shouldn't we when deer and other prey consider us to be a higher power?"

In other words, if Saphira is a higher power to the deer, why can't there be a higher power to Saphira?

Well, actually there is, and because writing the next 600-page book will no doubt take a while, author Christopher Paolini has plenty of time to get his subjects thinking straight. After all, he is a higher power to both Oromis and Saphira.

Sunday, October 16, 2005

Amish Entrepreneurs

I recently finished a book about how the Amish are leaving the farm because of the high cost of farmlan, and are starting businesses, and how, despite having less than a high school education, with little experience in business, with very little familiarity with technology and, of course, with limits on how they can use technology, they are doing better at it than a lot of non-Amish.

I was particularly struck by this statistic, at the start of chapter 12 of Amish Enterprise, by Donald Kraybill and Steven Nolt:

Wow! How do they do it?

Well, the authors don't lump all the reasons for their success in one place, so I'll miss some, but here are the reasons I remember:

- They start small, often in their homes or in outbuildings near their home.

- They start (and stay) simple, which keeps their costs down. Their culture frowns on luxuries and showing off, either for them personally or in their businesses. So their overhead is low. They're not big on splashy advertising, either, so they - to some extent - avoid one of the big costs of business - marketing. (I guess when you avoid self-promotion, you really have to rely on word of mouth.)

- They don't mind hard work (they're coming from a farming background, remember) and are willing to work long hours. What's interesting is that they don't regard work and family as separate and competing. They try (not always successfully) to make it a family activity. Mom and Dad run the business and the kids sweep up or do other chores.

- They are scrupulously honest. People like doing business with people they trust. Duh!

- They focus on high quality.

- They live simply, which means "cheaply," so they can charge less and still make a profit, and since they're not spending the money on indulgences, much of the money they make goes back into building their businesses.

- They help each other. If a business is having trouble, other Amish business people help out.

There are other things, like - well - just being Amish, which attracts customers because of its novelty, but the other things I can think of aren't transferable. If you pick up the book, by the way, it's a sociological study, not really a business book

This also reminds me of a most excellent business book, called Good to Great (Jim Collins), which I read a while ago. The one thing I remember without reviewing is what the author regards as the main reason why some companies that are just chugging along in their industry suddenly (apparently suddenly) break out of the pack and become excellent and remain so for at least 15 years. It's not what you think. It's not a great plan; it's not a brilliant CEO; it's not clever financing or deal making; it's not a revolutionary product, it's not "getting control of the purse strings" - it's a humble but determined CEO. He (or she) is determined to make the company successful, but figures he doesn't have the skills to do it himself, so he humbly hires the best possible people.

I was particularly struck by this statistic, at the start of chapter 12 of Amish Enterprise, by Donald Kraybill and Steven Nolt:

The story of Amish enterprise is largely a story of success, with only scattered tarnishes of failure. The default rate among small business in general is rather sobering, however. Nearly one-quarter of new American firms fold within two years, and some 63 percent close their doors within six years. During the 1980s, the rate of business failure nearly matched that of the Great Depression. The Amish launched more than 40 percent of their business ventures in the 1980s, but surprisingly, fewer than 5 percent of the Amish operations failed.

Wow! How do they do it?

Well, the authors don't lump all the reasons for their success in one place, so I'll miss some, but here are the reasons I remember:

- They start small, often in their homes or in outbuildings near their home.

- They start (and stay) simple, which keeps their costs down. Their culture frowns on luxuries and showing off, either for them personally or in their businesses. So their overhead is low. They're not big on splashy advertising, either, so they - to some extent - avoid one of the big costs of business - marketing. (I guess when you avoid self-promotion, you really have to rely on word of mouth.)

- They don't mind hard work (they're coming from a farming background, remember) and are willing to work long hours. What's interesting is that they don't regard work and family as separate and competing. They try (not always successfully) to make it a family activity. Mom and Dad run the business and the kids sweep up or do other chores.

- They are scrupulously honest. People like doing business with people they trust. Duh!

- They focus on high quality.

- They live simply, which means "cheaply," so they can charge less and still make a profit, and since they're not spending the money on indulgences, much of the money they make goes back into building their businesses.

- They help each other. If a business is having trouble, other Amish business people help out.

There are other things, like - well - just being Amish, which attracts customers because of its novelty, but the other things I can think of aren't transferable. If you pick up the book, by the way, it's a sociological study, not really a business book

This also reminds me of a most excellent business book, called Good to Great (Jim Collins), which I read a while ago. The one thing I remember without reviewing is what the author regards as the main reason why some companies that are just chugging along in their industry suddenly (apparently suddenly) break out of the pack and become excellent and remain so for at least 15 years. It's not what you think. It's not a great plan; it's not a brilliant CEO; it's not clever financing or deal making; it's not a revolutionary product, it's not "getting control of the purse strings" - it's a humble but determined CEO. He (or she) is determined to make the company successful, but figures he doesn't have the skills to do it himself, so he humbly hires the best possible people.

Sunday, August 28, 2005

Rockefeller's Philanthropy

A while ago I finished Titan, about the curious life of John D. Rockefeller, the founder of Standard Oil. Author Ron Chernow paints a picture of a contradictory and confusing but fascinating man, on the one side a hard-edged businessman who would cross over into illegal and immoral practices in his quest to succeed, but on the other side, a man who was actually quite generous and fair in his business practices and - far more interesting - a man who did amazing things with his money.

To say all I can on Rockefeller's positive side, he thought he was doing good - all the time. He thought cooperation in the oil industry was better than competition, so he tried to create a monopoly (he never quite succeeded). He actually overpaid for oil refineries and people sometimes started refineries just so Standard Oil would buy them - at inflated prices. Rockefeller was scrupulous in paying his debts, he never took on the trappings of nobility, as did some of his rich contemporaries, he always attended a simple Baptist church rather than moving up to some socially more acceptable church, and he tried to provide fuel to the world at cheap prices. And, as I mentioned, he gave generously, and when he did he seldom put his name on things ("Do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing"), as did Andrew Carnegie.

On the negative side, if companies refused to deal with him he tried to drive them out of business, and in doing that he bribed public officials, tried (and failed) to block a competitor's pipeline by buying up land in its path, manipulated railroad prices, tactically undersold competitors to drive them out of business, and so forth. When the federal government wanted to regulate the new post-Civil War interstate commerce, Rockefeller had provided them with a handy list of what to legislate against.

How Rockefeller internally reconciled some of his practices to his Christian faith, I have no idea. Chernow certainly doesn't seem to have figured that out either.

Anyway, his philanthropies were amazing! There his Christianity shone.

Hookworm, once a debilitating problem in the Southern US states, is no longer a big problem. Why? Because Dr. Charles Stiles discovered it could be cured with some cheap medicine, and though his discovery was met with ridicule, Rockefeller believed, and basically paid to erradicate the problem. Rockefeller also started a public-private partnership to build thousands of schools across the South. He founded the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, the first medical research lab in the country, whose discoveries have saved thousands if not tens of thousands of lives. He was also the money behind the founding of the University of Chicago. Lots of other stuff, too.

What strikes me about his giving was that it was thoughtful and focused and for the most part the results of his giving could be fairly precisely measured.

It occurs to me that there are problems - such as the ones Rockefeller focused on - that can pretty much be solved once and for all, but there are other kinds of problems ("the poor you will have with you always") that are less amenable to a one-time solution. Necessary as it may be to give to charities addressing the less solvable problems, I suspect that the better an organization can define a problem and measure success in combating it, the easier it will be to persuade people to contribute.

To say all I can on Rockefeller's positive side, he thought he was doing good - all the time. He thought cooperation in the oil industry was better than competition, so he tried to create a monopoly (he never quite succeeded). He actually overpaid for oil refineries and people sometimes started refineries just so Standard Oil would buy them - at inflated prices. Rockefeller was scrupulous in paying his debts, he never took on the trappings of nobility, as did some of his rich contemporaries, he always attended a simple Baptist church rather than moving up to some socially more acceptable church, and he tried to provide fuel to the world at cheap prices. And, as I mentioned, he gave generously, and when he did he seldom put his name on things ("Do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing"), as did Andrew Carnegie.

On the negative side, if companies refused to deal with him he tried to drive them out of business, and in doing that he bribed public officials, tried (and failed) to block a competitor's pipeline by buying up land in its path, manipulated railroad prices, tactically undersold competitors to drive them out of business, and so forth. When the federal government wanted to regulate the new post-Civil War interstate commerce, Rockefeller had provided them with a handy list of what to legislate against.

How Rockefeller internally reconciled some of his practices to his Christian faith, I have no idea. Chernow certainly doesn't seem to have figured that out either.

Anyway, his philanthropies were amazing! There his Christianity shone.

Hookworm, once a debilitating problem in the Southern US states, is no longer a big problem. Why? Because Dr. Charles Stiles discovered it could be cured with some cheap medicine, and though his discovery was met with ridicule, Rockefeller believed, and basically paid to erradicate the problem. Rockefeller also started a public-private partnership to build thousands of schools across the South. He founded the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, the first medical research lab in the country, whose discoveries have saved thousands if not tens of thousands of lives. He was also the money behind the founding of the University of Chicago. Lots of other stuff, too.

What strikes me about his giving was that it was thoughtful and focused and for the most part the results of his giving could be fairly precisely measured.

It occurs to me that there are problems - such as the ones Rockefeller focused on - that can pretty much be solved once and for all, but there are other kinds of problems ("the poor you will have with you always") that are less amenable to a one-time solution. Necessary as it may be to give to charities addressing the less solvable problems, I suspect that the better an organization can define a problem and measure success in combating it, the easier it will be to persuade people to contribute.

Friday, August 19, 2005

Freddy the Pig

I enjoy reading to my son a bit every night. He especially likes talking-animal books, so we started off with C.S. Lewis's Narnia Chronicles (awesome!), then we read several of Brian Jacques' Redwall series (quite good). We tackled Robin Hood, King Arthur, Treasure Island, Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, Jeanne Duprau's City of Ember (excellent!) and The People of Sparks (very good), Eragon, Booth Tarkington's Penrod and Penrod and Sam (old and excellent but with some racist - though not intentionally malicious - overtones), Despereaux (okay), Time Stops for No Mouse (good) and The Sands of Time (good), by Michael Hoeye, Ken Oppel's Silverwing (okay), Sunwing (okay), and Firewing (weird), A Cricket in Times Square, and we just finished Lloyd Alexander's series, The Book of Three (first book, fair, others, excellent). But now, what to read? What to read?

Well, for some reason I thought of a series I loved as a child, Walter Brooks Freddy the Pig books. I thought these 26-or-so books were long out of print, but - as I discovered in perusing Amazon - they have been brought back. Happy day! All's right with the world! We picked up Freddy the Cowboy at the library and are reading and enjoying it. I'd have preferred to start with Freddy the Detective, but you start where you can.

Here's a silly snippet. Freddy the pig is asking Quik (a mouse) if Howard (another mouse) can come for a visit:

My son likes it and so do I, so I think we have reading material to keep us busy for a long time.

Anyway, help revive the Freddy books! There's probably one or two of them left in your public library. Try one, and if your kids (or you) like it, the whole set is available on Amazon.

Well, for some reason I thought of a series I loved as a child, Walter Brooks Freddy the Pig books. I thought these 26-or-so books were long out of print, but - as I discovered in perusing Amazon - they have been brought back. Happy day! All's right with the world! We picked up Freddy the Cowboy at the library and are reading and enjoying it. I'd have preferred to start with Freddy the Detective, but you start where you can.

Here's a silly snippet. Freddy the pig is asking Quik (a mouse) if Howard (another mouse) can come for a visit:

"I suppose it'll be all right," he [Quik] said. "If he doesn't eat us out of house and home. I never knew a field mouse yet who didn't eat like a pi- I mean, like a pinguin," he said hurriedly.

"What's a pinguin?" Jinx [the cat] asked, and Howard said: "I think he means a penguin. They're very greedy creatures, though seldom seen in this neighborhood."

Quik grinned at him gratefully, but Freddy said: "Penguin nothing! He started to say 'pig' and then couldn't change it to anything that made sense."

My son likes it and so do I, so I think we have reading material to keep us busy for a long time.

Anyway, help revive the Freddy books! There's probably one or two of them left in your public library. Try one, and if your kids (or you) like it, the whole set is available on Amazon.

Sunday, August 07, 2005

Gouge Out Your Eye

And if your right eye causes you to sin, pluck it out, and cast it from you: for it is better for you that one of your members should perish, than that your whole body should be cast into hell. And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off, and cast it from you: for it is better for you that one of your members should perish, than that your whole body should be cast into hell. - Matthew 5:29-30

When Jesus said, "If your right eye causes you to sin, pluck it out" he was - I've heard - speaking metaphorically. Well... maybe. But maybe not. Perhaps instead he was giving a literal reply to a bad excuse he'd heard once too often.

I think Jesus was responding to the whine - probably as prevalent then as it is now - that goes like this: "Well, I just can't help it, I've got a wandering eye." Or, in the case of the hand, "I can't help it. I just have sticky fingers."

Okay, Jesus says, sighing a bit, I imagine, if it is really your eye that is dragging you into sin, then you really better gouge it out.

I can hear the whiner responding, "Uhhh, well, um, okay. I didn't literally mean my eye causes me to sin. My eye only does what I tell it to do."

Precisely!

And this, I think, is just what Jesus is trying to communicate. Don't blame your hand or eye. The sin comes from your heart, and you know it, and that is what needs to change.

When Jesus said, "If your right eye causes you to sin, pluck it out" he was - I've heard - speaking metaphorically. Well... maybe. But maybe not. Perhaps instead he was giving a literal reply to a bad excuse he'd heard once too often.

I think Jesus was responding to the whine - probably as prevalent then as it is now - that goes like this: "Well, I just can't help it, I've got a wandering eye." Or, in the case of the hand, "I can't help it. I just have sticky fingers."

Okay, Jesus says, sighing a bit, I imagine, if it is really your eye that is dragging you into sin, then you really better gouge it out.

I can hear the whiner responding, "Uhhh, well, um, okay. I didn't literally mean my eye causes me to sin. My eye only does what I tell it to do."

Precisely!

And this, I think, is just what Jesus is trying to communicate. Don't blame your hand or eye. The sin comes from your heart, and you know it, and that is what needs to change.

Saturday, July 30, 2005

Communism That Works

I've never been a communist, never wanted to be one, and never thought communism worked. But on that last point, while I'm confident I'm generally right, there's a group that proves me partially wrong.

I just finished a book on quite an interesting group of people, called the Hutterites, an Anabaptist Protestant group who date back to the Reformation. The Hutterites came to the conclusion that they should live communally, and have been doing so almost without interruption since the 1500s. Because of persecution they left Moravia (in what is now the Czech Republic) for the Ukraine, then moved to North America in the 1870s, and now they live in Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan in Canada and in Montana and the Dakotas in the United States.

That a group has managed to live for such a long time communally strikes me as quite amazing since so many other communal groups have utterly failed. Here are a few of my thoughts about why they have survived:

Far from being atheistic - as was Russian communism - the Hutterites are deeply religious. They believe their reward is in heaven, and so they don't feel much need to "succeed" - in a financial sense - here on earth.

They're under no silly illusion that communal living is a utopia. They believe people have sinful tendencies, even in their "colonies," as they call their communes, so nobody is disillusioned when someone does something unchristian.

Their colonies are relatively small, numbering about 80 to 150. It seems to me that a smaller group like this can maintain a family feeling whereas a larger group cannot. In fact, the book, Hutterite Society (by John A Hostetler), makes this point, that the larger groups become prone to factions. To deal with that, the Hutterites intentionally split the colonies and create daughter colonies when they become too big.

They maintain a cultural distance from their neighbors. Their colonies are in isolated locations, the people don't mix much with non-Hutterites, they dress differently, they speak German as a first language (though they also learn English). I suspect this cultural distance makes colony members feel less at home outside the colony and thus makes it harder for colony members to leave, but at the same time I'd guess it probably annoys their neighbors, whom I suspect may feel looked-down-upon by the Hutterites.

They strongly teach their traditions but de-emphasize higher education, which they feel isn't useful for farm life and leads to independent thinking (they're probably right) and thus to a breakdown of communal life.

Although the Hutterites have not only survived, but grown dramatically in numbers, one thing that strikes me about their growth is that it is almost entirely by having children. Very few non-Hutterites ever become Hutterites.

I suspect this is because of the cultural distance I mentioned. I have a theory that for churches to grow by attracting new members, there is a sweet spot in cultural positioning. If the church is too far removed from society (as are the Hutterites and the Amish), growth by conversion drops to just about nothing. On the other hand, churches that simply reflect society have nothing to offer the seeker. If the church is just the same as the everyday world, why bother going?

I think that sweet spot for most churches is just to obey Christ. For me, that is adequately removed from everyday society. If you go a lot further, into cultural isolation, as do the Hutterites and Amish, I think you can minimize people defecting from Christ to the world, but the cost will be to minimize defections from the world to Christ.

I just finished a book on quite an interesting group of people, called the Hutterites, an Anabaptist Protestant group who date back to the Reformation. The Hutterites came to the conclusion that they should live communally, and have been doing so almost without interruption since the 1500s. Because of persecution they left Moravia (in what is now the Czech Republic) for the Ukraine, then moved to North America in the 1870s, and now they live in Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan in Canada and in Montana and the Dakotas in the United States.

That a group has managed to live for such a long time communally strikes me as quite amazing since so many other communal groups have utterly failed. Here are a few of my thoughts about why they have survived:

Although the Hutterites have not only survived, but grown dramatically in numbers, one thing that strikes me about their growth is that it is almost entirely by having children. Very few non-Hutterites ever become Hutterites.

I suspect this is because of the cultural distance I mentioned. I have a theory that for churches to grow by attracting new members, there is a sweet spot in cultural positioning. If the church is too far removed from society (as are the Hutterites and the Amish), growth by conversion drops to just about nothing. On the other hand, churches that simply reflect society have nothing to offer the seeker. If the church is just the same as the everyday world, why bother going?

I think that sweet spot for most churches is just to obey Christ. For me, that is adequately removed from everyday society. If you go a lot further, into cultural isolation, as do the Hutterites and Amish, I think you can minimize people defecting from Christ to the world, but the cost will be to minimize defections from the world to Christ.

Tuesday, June 28, 2005

Visiting Saddleback Church

I've heard about Saddleback Church for years, so finally, last Sunday, my wife and I went, just to see what it is like. If you are not familiar with Saddleback, it is the church pastored by Rick Warren, author of The Purpose Driven Life.

The church is in Lake Forest, California, an Orange County town I'd never heard of except in connection with the church. The town is located somewhat inland, in a developing area that is still largely open. Huge tracts of land are still undeveloped. Also, while I'm sure the locals know how to avoid them, the main highways that take you to Lake Forest are toll roads, which are quite rare in California.

I'm certain Saddleback draws people who live far from Lake Forest, and I'd guess that many of those people have to pay the road toll to get there. That they're willing to do so is impressive.

The "driveway" to Saddleback, if you can call it that, is enormous. It is actually a road, Saddleback Parkway, which has its own traffic light at the main drag. It resembles the entrance to a mall, complete with a large but understated sign on a wall on the side of a berm.

As we drove in, the long driveway reminded us a bit of Legoland, with signs along the road welcoming us, and a very proficient staff that guided us to a parking spot. It was easy in and easy out, with the same roadside signs on the way out, this time thanking us for visiting.

The church campus reminded me of something between a park and an outdoor mall. In front of the main sanctuary (or whatever they call it) are some large, permanent plastic-walled tents. In each of them is an alternative service. The music is apparently different in each one, but the preaching - piped in by video from the sanctuary - is the same.

You approach the main building through a park-like mall area, with a stream, grassy hillock and various out-buildings, such as a coffee cafe. Then you climb some broad stairs, with a waterfall gurgling down the middle, and get to the sanctuary, which is modern and attractive but actually rather understated. I get the feeling they hired a mall architect and an amusement park architect and said, "Give it a mall-amusement park feeling and efficiency, but tone it down so it's not glitzy."

We were welcomed as we approached the sanctuary by greeters. Immediately inside, but outside the main meeting area, was an area apparently for parents with fussy kids. There was a video feed so they could participate in the service. We went in and were shown our seats by ushers who knew exactly where the few remaining empty seats were.

It appears the sanctuary is a multi-purpose room. Chairs on the floor appeared to be movable, and the seating in the back appeared to be on some sort of telescoping structure that would allow it all to be shoved back against the wall. Where we sat it was all stadium seating.

We got in a bit late and missed most of the music, but it seemed to be mostly praise songs. The front of the sanctuary was a low stage, with a simple metal podium for the speaker surrounded by colored bottles, which, it turned out, were to illustrate the biblical story of the widow who filled many bottles with a single small bottle of oil. Everything was expertly choreographed.

Behind and above the stage and running across the front of the sanctuary was - rather oddly - sort of a woodland scene, with trees and stuff. Curious.

The left and right walls of the sanctuary were made of clear glass, and on one side I could see people seated outside, some under patio umbrellas, but looking in. I imagine there were speakers so these sun-lovers could hear the service while watching it through the windows. The congregation was mostly white, with Asians and some Blacks and Hispanics.

The sermon was biblical, skillful and cheerful. The pastor (not Rick Warren today) was dressed casually, as was most of the congregation. The podium was flanked on either side by two giant video screens, showing the pastor close up, or switching to a slide to illustrate one of his points. Bible verses were chosen from various translations (I actually prefer sticking to one good translation). To illustrate one of his points, he brought out a woman from the congregation who described how God had used the death of her daughter to help her minister to other people.

In the bulletin (a four-color and very professional publication) was a note saying that visitors shouldn't feel obliged to give, that giving is for those who call Saddleback their church home. Cool! I was actually a bit surprised when they passed the plate. It was during the closing moments of the service and there wasn't a word said about it. The plate was just there all of a sudden. No announcement that it was coming; no pleading to give; nothing. I found this understated approach quite refreshing, and judging from the grounds, it apparently works.

After the service we wandered through an outdoor book store in front of the sanctuary, looked over some of the outlying buildings, and headed out.

A few thoughts:

While adopting modern marketing, it seems Saddleback has taken care not to become crass or commercial, though I think that with a moment's inattention it could go over the edge into glitz and self-indulgence. I think it should be very careful to avoid that.

Also, I think other churches shouldn't emulate Saddleback blindly, but should pick and choose what to implement. For example, it won't be possible for most churches in a city to have a walking mall and a huge parking lot. Land is too expensive, and besides, there also need to be neighborhood churches, which this definitely is not.

Finally, I think that a lot of what I have described is of secondary or tertiary importance. No matter how well organized or attractive or artistically choreographed, I don't think Saddleback would work without good, accessible and biblically focused teaching. Take that away and I think it would stagnate and die just like any other church that loses its way.

Overall, despite the long drive, it was well worth the visit. Blessings on you, Saddleback!

The church is in Lake Forest, California, an Orange County town I'd never heard of except in connection with the church. The town is located somewhat inland, in a developing area that is still largely open. Huge tracts of land are still undeveloped. Also, while I'm sure the locals know how to avoid them, the main highways that take you to Lake Forest are toll roads, which are quite rare in California.

I'm certain Saddleback draws people who live far from Lake Forest, and I'd guess that many of those people have to pay the road toll to get there. That they're willing to do so is impressive.

The "driveway" to Saddleback, if you can call it that, is enormous. It is actually a road, Saddleback Parkway, which has its own traffic light at the main drag. It resembles the entrance to a mall, complete with a large but understated sign on a wall on the side of a berm.

As we drove in, the long driveway reminded us a bit of Legoland, with signs along the road welcoming us, and a very proficient staff that guided us to a parking spot. It was easy in and easy out, with the same roadside signs on the way out, this time thanking us for visiting.

The church campus reminded me of something between a park and an outdoor mall. In front of the main sanctuary (or whatever they call it) are some large, permanent plastic-walled tents. In each of them is an alternative service. The music is apparently different in each one, but the preaching - piped in by video from the sanctuary - is the same.

You approach the main building through a park-like mall area, with a stream, grassy hillock and various out-buildings, such as a coffee cafe. Then you climb some broad stairs, with a waterfall gurgling down the middle, and get to the sanctuary, which is modern and attractive but actually rather understated. I get the feeling they hired a mall architect and an amusement park architect and said, "Give it a mall-amusement park feeling and efficiency, but tone it down so it's not glitzy."

We were welcomed as we approached the sanctuary by greeters. Immediately inside, but outside the main meeting area, was an area apparently for parents with fussy kids. There was a video feed so they could participate in the service. We went in and were shown our seats by ushers who knew exactly where the few remaining empty seats were.

It appears the sanctuary is a multi-purpose room. Chairs on the floor appeared to be movable, and the seating in the back appeared to be on some sort of telescoping structure that would allow it all to be shoved back against the wall. Where we sat it was all stadium seating.

We got in a bit late and missed most of the music, but it seemed to be mostly praise songs. The front of the sanctuary was a low stage, with a simple metal podium for the speaker surrounded by colored bottles, which, it turned out, were to illustrate the biblical story of the widow who filled many bottles with a single small bottle of oil. Everything was expertly choreographed.

Behind and above the stage and running across the front of the sanctuary was - rather oddly - sort of a woodland scene, with trees and stuff. Curious.

The left and right walls of the sanctuary were made of clear glass, and on one side I could see people seated outside, some under patio umbrellas, but looking in. I imagine there were speakers so these sun-lovers could hear the service while watching it through the windows. The congregation was mostly white, with Asians and some Blacks and Hispanics.

The sermon was biblical, skillful and cheerful. The pastor (not Rick Warren today) was dressed casually, as was most of the congregation. The podium was flanked on either side by two giant video screens, showing the pastor close up, or switching to a slide to illustrate one of his points. Bible verses were chosen from various translations (I actually prefer sticking to one good translation). To illustrate one of his points, he brought out a woman from the congregation who described how God had used the death of her daughter to help her minister to other people.

In the bulletin (a four-color and very professional publication) was a note saying that visitors shouldn't feel obliged to give, that giving is for those who call Saddleback their church home. Cool! I was actually a bit surprised when they passed the plate. It was during the closing moments of the service and there wasn't a word said about it. The plate was just there all of a sudden. No announcement that it was coming; no pleading to give; nothing. I found this understated approach quite refreshing, and judging from the grounds, it apparently works.

After the service we wandered through an outdoor book store in front of the sanctuary, looked over some of the outlying buildings, and headed out.

A few thoughts:

While adopting modern marketing, it seems Saddleback has taken care not to become crass or commercial, though I think that with a moment's inattention it could go over the edge into glitz and self-indulgence. I think it should be very careful to avoid that.

Also, I think other churches shouldn't emulate Saddleback blindly, but should pick and choose what to implement. For example, it won't be possible for most churches in a city to have a walking mall and a huge parking lot. Land is too expensive, and besides, there also need to be neighborhood churches, which this definitely is not.

Finally, I think that a lot of what I have described is of secondary or tertiary importance. No matter how well organized or attractive or artistically choreographed, I don't think Saddleback would work without good, accessible and biblically focused teaching. Take that away and I think it would stagnate and die just like any other church that loses its way.

Overall, despite the long drive, it was well worth the visit. Blessings on you, Saddleback!

Sunday, June 05, 2005

Giving Back to the Community

Every once in a while I'll hear someone say that companies should "give back to their communities."

In a strict sense, I think this is nonsense.

When someone talks about giving back, he or she is essentially saying the company took something from the community that needs to be repaid.

But if I have a business that sells, say, shoes, how am I taking from the community? I'm providing shoes to my customers and my customers are providing money to me. When the shoes sell, the transaction is complete and nobody owes anybody anything else. Everybody is benefitted.

However, in many cases, companies go beyond that. They pay various local fees and taxes, they provide employment, and their employees go out and spend the money they earn throughout the community, benefiting even more people. So I'd argue that companies are already giving to the community.

None of this is to argue that giving to the community is wrong. I think giving - by companies or individuals - is a kind thing to do, that it can make the community a more closely knit and pleasant place to live, and it's great PR. But to suggest as any sort of general rule that businesses are somehow soaking something out of the community that needs to be repaid does not impress me in the slightest.

In a strict sense, I think this is nonsense.

When someone talks about giving back, he or she is essentially saying the company took something from the community that needs to be repaid.

But if I have a business that sells, say, shoes, how am I taking from the community? I'm providing shoes to my customers and my customers are providing money to me. When the shoes sell, the transaction is complete and nobody owes anybody anything else. Everybody is benefitted.

However, in many cases, companies go beyond that. They pay various local fees and taxes, they provide employment, and their employees go out and spend the money they earn throughout the community, benefiting even more people. So I'd argue that companies are already giving to the community.

None of this is to argue that giving to the community is wrong. I think giving - by companies or individuals - is a kind thing to do, that it can make the community a more closely knit and pleasant place to live, and it's great PR. But to suggest as any sort of general rule that businesses are somehow soaking something out of the community that needs to be repaid does not impress me in the slightest.

Friday, June 03, 2005

CompUSA's Inconvenient Warranty

A while ago I bought a Sony laptop at CompUSA. I was talked into the extended warranty because they said they would fix my computer if anything goes wrong with it and I knew they did repairs on the premises. It'll make everything convenient, I was told. No worries.

Well, something did go wrong. The power plug is loose in the socket so it doesn't charge reliably. Trivial, right? Should take an hour to fix.

Not even! Alhough they say they do computer repairs on the premises, they wanted to send the laptop off to Sony, and, they said, that'll take about two weeks.

Convenient? Not within a hundred miles of being convenient. I'm supposed to be without my computer for two weeks because of a silly plug? You're packing my computer off to who knows where with all my data on it? I don't think so! If all the big retailers offer as rotten a service as CompUSA, then there's a competitive opening as big as a locomotive for a computer sales company that offers good local service.

Well, something did go wrong. The power plug is loose in the socket so it doesn't charge reliably. Trivial, right? Should take an hour to fix.

Not even! Alhough they say they do computer repairs on the premises, they wanted to send the laptop off to Sony, and, they said, that'll take about two weeks.

Convenient? Not within a hundred miles of being convenient. I'm supposed to be without my computer for two weeks because of a silly plug? You're packing my computer off to who knows where with all my data on it? I don't think so! If all the big retailers offer as rotten a service as CompUSA, then there's a competitive opening as big as a locomotive for a computer sales company that offers good local service.

Sunday, May 29, 2005

Topical Bible Study Idea

I recently had an idea that might be good for Bible study groups. I haven't tried it so I don't know how well it would work, but here it is:

To study a book in the Bible is fairly straightforward for a small group. Either a leader goes through it, or group members rotate in leading the study, but in either case the study proceeds sequentially, from beginning to end.

But to study a topic is harder to do because you need to know what the whole Bible or the whole New Testament or Old Testament says about the topic. I've seen some pretty poor topical teaching done as a result. Often such teaching misses important Bible passages about the topic.

So what if a study group divided the Bible into chapters, and each member of the group was responsible for learning what a set of chapters has to say about the topic. By dividing the task it becomes easier for everybody and you get to see what the Bible really says, rather than relying on secondary sources.

The New Testament has 260 chapters, so a 10-person Bible study group could study a New Testament topic in six sessions (260/10/6) if everybody is willing to cover a little more than four chapters between each session.

The whole Bible has 1,189 chapters, so the same study group could study a Bible topic in 12 sessions if everybody is willing to do about 10 chapters between each session.

I don't know how well this would work, but if anybody wants to give it a try I'd love to hear about it.

To study a book in the Bible is fairly straightforward for a small group. Either a leader goes through it, or group members rotate in leading the study, but in either case the study proceeds sequentially, from beginning to end.

But to study a topic is harder to do because you need to know what the whole Bible or the whole New Testament or Old Testament says about the topic. I've seen some pretty poor topical teaching done as a result. Often such teaching misses important Bible passages about the topic.

So what if a study group divided the Bible into chapters, and each member of the group was responsible for learning what a set of chapters has to say about the topic. By dividing the task it becomes easier for everybody and you get to see what the Bible really says, rather than relying on secondary sources.

The New Testament has 260 chapters, so a 10-person Bible study group could study a New Testament topic in six sessions (260/10/6) if everybody is willing to cover a little more than four chapters between each session.

The whole Bible has 1,189 chapters, so the same study group could study a Bible topic in 12 sessions if everybody is willing to do about 10 chapters between each session.

I don't know how well this would work, but if anybody wants to give it a try I'd love to hear about it.

Friday, May 20, 2005

Star-Wars: Excellent!

I just saw the latest Star Wars movie and it was amazing! I'm not a Star-Wars fanatic, but I thought it did a great job of tying the lose ends together and believably showing the turn of Anakin to the "dark side."

Which leads me to do a little philosophizing...

I wouldn't attend this movie looking for bulletproof philosophy. The notion that if "the Force" is "in balance" the universe would be at peace is just silly; as if having half the people be power-hungry murderers and the other half be peace-lovers would somehow provide a necessary balance to our world. Goofy. And then Obi Wan saying that "only the Sith speak of absolutes." Sigh. What is Obi Wan doing? Well, he's speaking an absolute. Obi, its not absolutes that get you into trouble, it's what absolutes you subscribe to.

But this whole Force thing is just a mandatory patina of Eastern philosophy over the very old fashioned - and very well told - tale of good vs. evil.

When you see it, notice the subtlety of evil. The confusion of Anakin. How difficult it is to see evil in ourselves. The appeal by the evil Chancellor to broad mindedness. How what is right and what is expedient get mixed. How it can sometimes be unclear what is the right thing to do, especially when there are conflicting accounts and interpretations and desires. How evil promises wonderful things but fails to keep its word.

Well worth the price of admission.

Which leads me to do a little philosophizing...

I wouldn't attend this movie looking for bulletproof philosophy. The notion that if "the Force" is "in balance" the universe would be at peace is just silly; as if having half the people be power-hungry murderers and the other half be peace-lovers would somehow provide a necessary balance to our world. Goofy. And then Obi Wan saying that "only the Sith speak of absolutes." Sigh. What is Obi Wan doing? Well, he's speaking an absolute. Obi, its not absolutes that get you into trouble, it's what absolutes you subscribe to.

But this whole Force thing is just a mandatory patina of Eastern philosophy over the very old fashioned - and very well told - tale of good vs. evil.

When you see it, notice the subtlety of evil. The confusion of Anakin. How difficult it is to see evil in ourselves. The appeal by the evil Chancellor to broad mindedness. How what is right and what is expedient get mixed. How it can sometimes be unclear what is the right thing to do, especially when there are conflicting accounts and interpretations and desires. How evil promises wonderful things but fails to keep its word.

Well worth the price of admission.

Saturday, May 07, 2005

Religious Politicking for Me, Not For Thee

I was both amused and annoyed at some of the junk that came out of a recent conference at the City University of New York to, ostensibly, expose "the real agenda of the religious far right."

First, this snip from the article referenced above:

Hello? Talk about calling other people evil and other points of view illegitimate! Here's what they said about conservative Christians at the same conference:

Okay, setting aside the gratuitous rudeness, the casual reader might - just might - be led to assume that these folks were condemning Machiavelli, Hitler, Stalin, Jim Jones and neo fascism, saying, in other words, that people who believe like them are evil and their viewpoints are illegitimate.

So, calling conservative Christians evil and their viewpoints illegitimate is okay, but if Edgar ran the country he wouldn't let conservative Christians do the same thing.

Edgar, you have totalitarian tendencies of precisely the same type you condemn.

Second point: The examples used at the conference of Christian intolerance were taken from the fringiest of fringe groups, who would like to re-institute the Old Testament law. You could live your entire Christian life without ever hearing of these groups or hearing their beliefs espoused. I've heard them discussed maybe three times in my fairly long Christian life.

But I'm afraid that some people may think that the difference between conservative Christianity and a belief that we should impose the Old Testament law is just a matter of degree, that the more biblically conservative you become, the closer you are to wanting to impose Old Testament law.

This is simply wrong. There are distinct theological differences here. Almost all Christian groups believe that while the law may give us glimpses into God's thinking, sort of as a shadow of a person gives an idea of what that person looks like, the law itself - except where it is reiterated in the New Testament - is over and done with and should never be brought back.

First, this snip from the article referenced above:

The Rev. Bob Edgar, a former Democratic congressman and general secretary of the National Council of Churches, strongly favors religious politicking but said in an interview that he draws the line when groups say "we are right and everyone else is evil" or claim that "another point of view is illegitimate."

Hello? Talk about calling other people evil and other points of view illegitimate! Here's what they said about conservative Christians at the same conference:

Although one speaker lamented Roman Catholicism's new "fundamentalist pope," the chief targets were evangelical Protestants -- whose tactics were compared with those of Machiavelli, Hitler, Stalin and Jim Jones of mass-suicide infamy.

Charles Strozier, director of a CUNY terrorism center, said the religious right, "emboldened in ways never seen before in American history," is promoting the "basically neo-Fascist schemes of the new Republicans."

Okay, setting aside the gratuitous rudeness, the casual reader might - just might - be led to assume that these folks were condemning Machiavelli, Hitler, Stalin, Jim Jones and neo fascism, saying, in other words, that people who believe like them are evil and their viewpoints are illegitimate.

So, calling conservative Christians evil and their viewpoints illegitimate is okay, but if Edgar ran the country he wouldn't let conservative Christians do the same thing.

Edgar, you have totalitarian tendencies of precisely the same type you condemn.

Second point: The examples used at the conference of Christian intolerance were taken from the fringiest of fringe groups, who would like to re-institute the Old Testament law. You could live your entire Christian life without ever hearing of these groups or hearing their beliefs espoused. I've heard them discussed maybe three times in my fairly long Christian life.

But I'm afraid that some people may think that the difference between conservative Christianity and a belief that we should impose the Old Testament law is just a matter of degree, that the more biblically conservative you become, the closer you are to wanting to impose Old Testament law.

This is simply wrong. There are distinct theological differences here. Almost all Christian groups believe that while the law may give us glimpses into God's thinking, sort of as a shadow of a person gives an idea of what that person looks like, the law itself - except where it is reiterated in the New Testament - is over and done with and should never be brought back.

Saturday, April 30, 2005

Nothing to Explain

I've been reading Bram Stoker's Dracula and happened upon a couple great quotes.

Dr. Abraham Van Helsing is about to explain about the supernatural. He says:

And, immediately following:

Oh, so true. So true.

Dr. Abraham Van Helsing is about to explain about the supernatural. He says: